- Home

- Renee Harrell

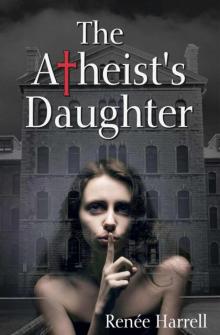

The Atheist's Daughter Page 3

The Atheist's Daughter Read online

Page 3

“A promise for an interview. In a month, if business improves.”

“That’s something.”

“It’s a kiss-off. I smiled prettily and left the application, anyway.” Kristin followed the path of the painter’s brush. “You’re not working on canvas.”

“I wanted to try hardboard this time.”

“It’s all curves and circles,” Kristin said. “That’s an awful lot of pink.”

“No pink at all, darling. There’s cadmium scarlet, yellow ochre, a little lead white. I’m trying for a dusky peach tone.” She examined the brush in her fingers. “This beauty is a new hog bristle brush, a Berkeley Number Seven. Special order and not exactly cheap. “

A needle of panic stabbed at Kristin. “How much?”

Becky wrinkled her nose, as if price didn’t matter.

“What are you painting, anyway?”

“Something a little bit different. More impressionist than realistic.”

“Your rep said everyone loves your landscapes. Your last show completely sold out.”

Sixteen paintings, each with a wonderful red dot in its lower right corner, she reflected. Each dot representing cash in the pocket and another bill paid on time. But Mom knows that.

You do know that, don’t you?

“Got a little tired of painting rustic weathered barns. Got a lot tired of painting tranquil country landscapes,” Becky said. “Aren’t you going to say hello to Susannah?”

Stretched across their worn flower-print sofa, the plump and nearly-naked Susannah Guitierrez wiggled her fingers in a greeting. Wearing only cotton panties, she posed atop a lavender bed sheet. She appeared remarkably comfortable with the rolls of flesh on her sixty-something year old body.

“Hi, sweetness,” she said merrily.

Kristin opened her mouth but no words came out. Finding Susannah undressed in her living room was barely more imaginable than opening the linen closet to discover an alligator chewing on the bath towels.

Her mother had painted portraits before, sure, but always on commission, with a check in hand. Those models had always worn clothing while posing.

This was completely different. Two years before, at the community pool, Susannah had covered herself in a modest one-piece bathing suit. A beach towel had hidden her body during the entire outing.

No one in the world will want this painting, Kristin thought. This isn’t art.

This is abstract pornography.

The doorbell rang, breaking her reverie. Using the opportunity to escape, she said, “I’ll get it.”

When I was eight years old, Susannah was my babysitter. My babysitter! Artist’s model or not, it’s wrong to see your babysitter with her breasts hanging out, no matter how many years have passed.

Opening the door, she found Gideon Hawkins in the doorway. Tall and slender, his brown hair was tucked behind his ears with one errant curl dangling down his forehead. Dressed in blue jeans and a loose shirt, he looked like anything but a preacher’s son.

His father, the Reverend Howard Hawkins, didn’t approve of his only child wearing jeans and an untucked shirt when a more respectable suit and tie was readily available in the bedroom closet.

He didn’t approve of his son’s friendship with Kristin Faraday, either.

“The atheist’s daughter?” she’d heard him say once, unhappiness in his voice. As far as she knew, he never said, “The girl they locked away?” or “The one with hallucinations?”

If he cared about such things, he kept them to himself. All he wanted to know was, did Kristin go to church?

She most certainly did not.

Hawkins kept one arm behind his back. When she tried to see what he was hiding, he shuffled sideways.

“Show me.”

Solemnly, he brought his arm forward. In his hand, he held a bouquet of flowers.

“Really? I mean, really?”

“These aren’t for you, Faraday. These are for your mother.”

She crossed her arms over her chest. “It won’t work, lame ass. She isn’t going to be bought for a handful of roadside posies.”

“Carnations. Besides, this isn’t a bribe. It’s a thank-you.”

She mock-slammed the door but he slid one foot in front of him. The door bounced weakly against his shoe.

“Jesus,” she said.

“Exactly.”

He headed for the living room. Her mother held her brush in the air as she considered her work. When he pushed the bouquet toward her, she smiled.

“Carnations,” Becky said. “They’re lovely.”

“Dorothy Parker said flowers were Heaven’s masterpiece.”

“No such thing as Heaven, young Hawk.” Becky shifted to reveal the painting on her easel. “What do you think?”

He puzzled over the curious shapes and colors on the board. A tinge of red crept into his cheeks as he discovered the vaguely carnal nature of her work.

“Well?”

Hawkins cleared his throat. “I, uh – I like your barns.”

“This isn’t a barn.”

“I’ve noticed.”

“Do you like it?”

He shuffled his feet uncomfortably. “It’s different.”

“Different good,” Becky said, “or different bad?”

His attention focused on the painting in front of him, he didn’t respond immediately. Kristin knew he hadn’t seen Susannah at the other end of the room. Wrapping the lavender bed sheet around her peach-colored body, the older woman walked toward the easel.

“It’s not just your barns,” Hawkins said to Becky. “I also like your landscapes.”

“Thank you.” At Becky’s words, he released a sigh of relief. She touched his sleeve before he could retreat. “I’m trying something different with this. Something a little less representational. If you have an opinion about it, I’d really like to know.”

He leaned toward the painting. “It’s mostly curls and circles.”

“I think the big circles are supposed to be my breasts,” Susannah said from behind him.

Hawkins jerked. Discovering the nearly-nude woman at his back, he crab-stepped away from the easel. His eyes flashed over the thin sheet covering Susannah, finding large patches of bare skin almost everywhere. An expression of horror played across his face.

Susannah studied Becky’s work. “I like it.”

Hawkins stared at her in amazement. Embarrassed, he dropped his gaze.

Finally, Kristin took pity on him. “The kitchen, Hawk. Let’s get some supper.”

He quickly followed after her. Placing the bowl in the microwave, she stabbed at its START button.

In a low voice, Hawkins said, “That has to be a sin.”

“What?”

“Ms. Guitierrez. What she’s wearing. What she isn’t wearing.”

“Count yourself lucky. She was in panties when I got here. Only in panties.”

His face wrinkled in contemplation of such a terrifying vision. “Okay, maybe it’s not a technical sin, sitting naked in somebody’s house. I mean, it’s not a covet thing, trust me, and there’s definitely no lust issue involved here. But there should be a law.”

“What kind of law?”

Speaking in a voice that brooked no argument, he said, “You should have to be much more attractive if someone is going to paint pink swirls and pretend it’s your bare body.”

“Those swirls aren’t really pink,” Kristin said. “Mom was using cadmium scarlet and yellow ochre.”

“What?”

“Plus, a little lead white. Mix ‘em together, it turns pink. Pink-ish. Skin tone, anyway.”

“Are you trying to make some kind of point here?”

“I’m torturing you with minutiae.”

“Why?”

“Punishment,” she said. “You brought flowers.”

“For your mother.” Pointedly, he added, “You’d know if I was lying.”

“I see what you’re doing. I mean, what you’re trying to do.”

Hawkins tugged a bar stool from beneath the counter top. Sliding onto it, he looked at Kristin with a guileless expression.

She said, “You’re trying to...to – seduce me through my mother.”

“Whatever it takes.”

The microwave dinged. “We’ve been friends since ninth grade. Can’t we leave it at that?”

“One time. That’s not so much to ask.”

She pulled on oven mitts.

Hawkins asked, “Have you ever done it?”

Holding the bowl, Kristin hip-bumped the microwave door into place. Placing the dish on a metal trivet, she peeled back its cellophane cover. Steam rose into the air.

“Want to know how many times I have?” Hawkins said.

“You’ve counted?” He nodded. “That’s beyond pitiful, Hawkman.”

“This Sunday,” he said. “You and me.”

“I’m busy on Sunday.”

“Yeah? Doing what?”

“Doing something else.” Reaching into a drawer, she removed a large serving spoon.

“I asked your Mom yesterday. She’s okay with it. She says it’s your decision.”

“Thus, the assortment of carnations.” She waggled the spoon at him. “Bring all the flowers you want, it isn’t going to matter. When the time comes I chose to do it – if such a time should ever come – it won’t be because you talked my mother into it.”

“Please.”

“See, that would have been a better way to start. Too late now.”

“Pretty please.”

“Forget it.” She shoved the spoon into the blue bowl’s mouth. “My first time? I’m not doing it this Sunday and I’m certainly not doing it while your father is in the building!”

Opening an upper cabinet, Hawkins pulled out two plates. “Dad wouldn’t say anything.”

“He’d notice, though. He’d be waiting at the door, wanting to talk to me after.”

Hawkins carried the plates to the counter top. “You know what everybody thinks, right? My best friend? Not trying it with me. Not ever.”

“I’ve seen it on t.v.”

“It’s not the same.”

“’No’ means ‘no’,” Kristin said firmly. “I’m not going to church with you.”

She dug into the bowl, pulling a thick glob of food from its center. Turning her spoon, she let the orange pasta clump fall onto Hawkins’ plate.

His face fell. “Mac and cheese? Again?”

Chapter Seven

From Kristin’s Diary

Mom’s hinting at it, just like last week.

And the week before that.

“You can always go to Hurley,” she tells me. “Get your two year degree.” She says this because, despite having a shiny high school diploma in hand, I still haven’t found a job.

Find a job? Hell, I can’t even get a job interview.

Somehow, life in Winterhaven manages to bump its Suck Score a little higher every day. Whenever I think things have reached bottom, cosmic forces conspire to dig a new, somehow deeper hole.

Mom doesn’t get it. Even if I did want to get an advanced degree, it wouldn’t be at Hurley. I imagine there are decent junior colleges out there somewhere but not in Winterhaven.

HJC isn’t exactly renowned, you know? At least, not in a good way.

The place really only offers three degrees. There’s gunsmithing and it’s a biggie, drawing students from across the state. Barton Hurley made a fortune in bullets and blood, everybody knows his history, and each semester brings another line of candidates eager to honor the Hurley name.

Not me.

I could go for an Associate Degree in Welding. Which used to offer the potential for a living wage until Hurley International decided to go truly international and moved both of its plants and its smoke-spewing foundry to Tuxtla, Mexico.

Which leaves option #3, a Hurley favorite, the General Degree. As in, “Generally, I don’t have any idea of what I’ll do with this degree.”

If I went to HJC, it would take another two years to get a piece of parchment I don’t even want. I’ve lost enough time in my life. I’m ready to move on.

I wish I could talk to Mom about it. I can’t because she’d panic at the thought of her child going to another city. That’s what over-protective mothers do. Even if I wanted to discuss my plans with her – something I most definitely do not want to do – she wouldn’t listen. She’d hate the idea of me leaving. She’d have a thousand reasons why I shouldn’t go.

Can’t go.

Must not go.

So I’ll stay through the summer, doing whatever I can for cash, then pack my suitcases for Ashfork. Once I’m there, I’ll find an apartment and get work.

All I want is a barely-there job, where people might glance at the name badge on their server’s blouse but can’t be bothered to remember it later. A job where nobody notices when the waitress’s face freezes and things seem a little wrong.

Then I’ll buy a car, nothing fancy but my own wheels, at last, at last....

IF I CAN SOMEHOW GET MORE MONEY.

Five hundred and eighty-nine dollars is all I have in the bank and I wouldn’t have that much if it wasn’t for last year’s job at the café. Six bills isn’t even enough for a bad set of wheels.

Besides, forget about buying a car, how is a few hundred dollars going to put a roof over my head? In what universe does that amount of money cover first month’s rent, last month’s rent, and a security deposit?

Ashfork is many things but it isn’t cheap. Without a job – a real job, and soon – I’ll be on the outside, looking in.

I’ll never leave Winterhaven.

No. No. Absolutely not.

Unacceptable.

Chapter Eight

In her bedroom, Kristin’s eyes were closed. She was asleep.

Dreaming.

In her dream, she found herself in the center of a lush, green meadow. A lovely cottage sat not far away from her, its charming round windows dotted by perfect droplets of dew. Leading to the cottage was a cobblestone bridge arching over a tiny stream. Past the bridge and its building, there was a densely wooded area. Where the sun peeked through the trees, the ground was nearly golden in color.

It was an idyllic place. Gazing at the scenery around her, she had to admit the setting was marvelous. In all of her life, she’d never been in a more perfect place.

So why does it all feel so wrong?

“Smurfs,” she muttered to herself. Yes!

Nothing was real here. This was a pretend place, somewhere you’d expect to find fairies or pixies or a colony of little blue Smurfs. They’d sing Smurf songs as they crossed their Smurf bridge, smiling Smurfily as they entered their petite jewel of a cottage. Papa Smurf would lead the parade and Smurfette would be waiting in the doorway.

A black thought intruded: You don’t belong here.

Where did that come from? she wondered.

Pixies and fairies were harmless creatures. Smurfs were just as imaginary and just as sweet. There wasn’t any reason to fear them or their ilk.

Nonetheless, the meadow darkened around her, growing less inviting. Although its creator clearly meant for the scene to appear inviting and friendly, it was born out of artifice. Its very existence was as calculated as the numbers in a banker’s ledger. Nothing true or honest would be found in this place.

The thought reappeared: You don’t belong here.

Well, Kristin thought, where else can I go?

Beyond the roof of the cottage were the woods. A shadow crouched behind the trees. Avoiding the fingers of sunshine streaking the meadow, the black shade crept from tree to tree, moving closer to the cottage.

Closer to me.

She looked away in fright, felt foolish about it, and forced herself to turn back.

There was nothing there.

For the first time, she felt something wet where the needles of grass nestled between her feet. Wiggling her toes, things felt strangely sticky. She wiped a forefing

er against the ground, the grass smearing as she touched it. When she looked at her finger, it carried a stripe of green across its tip.

“What is this?” She rubbed her thumb over the stripe of green. The color coated the thumb’s pad. She lifted her discolored fingers to her nose.

She liked the odor. She’d lived with it her entire life.

“Linseed oil is why my paints smell the way they do,” Becky told her once. “Once the oil evaporates, the paint dries and hardens.”

There was paint on her finger. Cinnaber Green, to be exact. One of the warmer shades of green, according to her mother.

No wonder things didn’t seem real here. They weren’t real. She was standing in the middle of an imaginary setting.

“It’s a landscape,” she said. “‘Afternoon at Holyford Creek’. One of Mom’s paintings!”

The cottage and its rock bridge had never existed in real life. Becky Faraday created it from scratch.

“People love chocolate box art,” she said, the day she started painting it, and she’d been proven right. Displayed in the gallery’s front window, this particular creation was red-tagged for an eager buyer before her latest show had officially opened.

“It’s a dream.” Kristin felt her stomach tighten. For the most part, her nights were blissfully empty of memories.

She hated dreams.

For the first time, she noticed she was wearing a pair of well-worn jeans and a long-sleeved purple top. Protruding from the shirt’s left breast pocket was a black-handled hog bristle paint brush. She pulled it from its pouch.

“A Berkeley Number Seven,” Becky’s voice said from out of nowhere. “Special order and not exactly cheap.”

In front of her was her mother’s easel. A rectangle of brown hardboard sat at the easel’s center mast.

What was I wearing at the start of the dream? Kristin wondered. Was the easel here the entire time?

Why didn’t she know?

None of this was familiar to her. It was only one more reason to hate dreams: The Dream Master’s world played by its own set of rules. The rules weren’t fair. Things popped in and out of existence and she had no control over any of it.

The Atheist's Daughter

The Atheist's Daughter